[I hope that this is another somewhat regular feature (although I expect the “Examples” posts will be more frequent) where I’ll highlight bad coat of arms designs by showing examples that were created with the visual designer.]

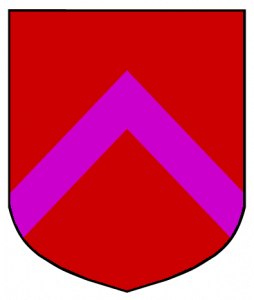

This first (for this blog) “bad design” violates one of (if not THE) primary rule of coat of arms design: the rule of tincture. The colors used are divided into metals and colors. Metals are argent (white) and or (gold.) Colors are everything else. The rule of tincture is basically that metals should not be placed so they touch metals and colors should not touch colors.

For example, if the background of the shield (the field) is red, a charge or ordinary such as a chevron (as in this example) should not be another color such as purple.

The rule of tincture exists because a coats of arms were originally used to determine combatants in a battle. If a particular shield was hard to discern then it would be hard to know that commander’s allegiance or rank. Exceptions to the rule of tincture exist, but they are extremely rare.

This design can be fixed in two ways:

- Change the red field to white or gold.

- Or change the purple chevron to white or gold.

If the chevron in the design above was a different type of ordinary that is sometimes “charged” (meaning one or more creatures or symbols are added on top of it) such as a bend or chief then the creatures or symbols on top of the ordinary would also have to follow the rule of tincture. If the ordinary was a metal, the primary colors of the charges would have to be non-metal colors and if the ordinary was a non-metal color the charges primary colors would have to be metals (gold or white.)

1. There are some well-known straight-up violations of this rule, most notably the arms of the Kingdom of Jerusalem: Argent a cross potent between four crosses or.

2. The tincture rule is more held to in English heraldry than continental heraldry. In part this is because continental heraldry commonly admits more colors than English heraldry and some of these are quite contrasty (sable on bleu celeste is quite easy to distinguish, for instance).

3. Even in England, the rule isn’t inviolate. For instance: Per saltire argent and azure, a saltire gules–GAGE, Hengrave, Suffolk

4. A third method of fixing the arms to comply with the rule would be to change the chevron to a metal but void it with a color: Gules, a chevron argent voided purpure (for instance). This would maintain the (horrific, IMO 😎 original color scheme while still following the rules.

Thanks Doug. I knew of the arms of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, but there seemed to be emphasis on the idea that there are very few exceptions. However, my source for this was definitely rooted in English heraldry.

It should be noted that Furs are technically not considered colours, as you’ve maintained, but rather a seperate category to themselves. While in modern (and in period) heraldry, furs are considered “neutral”, and thus can have either metals or colours placed upon them, its often good to treat them as their predominate colour.

For example, Ermine (white with black spots) is treated as a metal; Erminois (black with yellow spots) is treated as a colour; and vair (blue and white) is treated as neutral.

Yes, I am struggling for another term that combines tinctures and furs and came up with “colors” in the software. If you’ve got a suggestion I’d love to hear it.